Thoughts on the Art of Bonnie Bolton - Commentary by Warren Obluck

Bonnie Bolton doesn't talk much about painting. She knows very well the art of her times and the 20th Century in general. It's just not something she dwells on.

She far prefers action to talk. And so you will find her early most every morning aglow in the solitude of her studio, where she works steadily into the afternoon.

She paints in an expressive, seemingly naive style. Yet her painting, like her assemblages, is remarkably sophisticated.

Some of the best of Bolton's works refer to dreams or barely conscious memories of her childhood world - dreams and the unconscious, both proud banners of the Surrealist movement of the 1920's that found beauty in the unrecognized, the unexpected and the magical.

But although her work may be touched by Surrealist characteristics, it would be wrong to link Bolton too closely to that movement. She is no more and no less a Surrealist than was the great master of assemblage, Joseph Cornell.

Cornell spent a great deal of energy trying to fend off the Surrealists in the 1930s and '40s who wanted to incorporate him unreservedly into their ranks. But Cornell, like Bolton, rejects the movement's fascination with sensationalism, violence and eroticism.

Each buys into its idea of "unexpected juxtapositions," however, as they do into Marcel Duchamp's use of found objects. And they both pay careful attention to manifestations of their unconscious lives.

The Surrealists, of course, didn't give up easily. As late as 1939, Salvador Dali declared that Cornell's was "the only truly Surrealist work to be found in America."

Bolton's meticulously crafted assemblages - let's call them shadow boxes - tell stories. Some are simple, some more complicated.

Each is charged not only with a sly charm but with a kind of nostalgic melancholy - what the Brazilians call saudade, a yearning for something for someone that was loved but is no longer there. It is this sense of longing that lends universality to her shadow boxes and allows viewers to build their own stories next to hers.

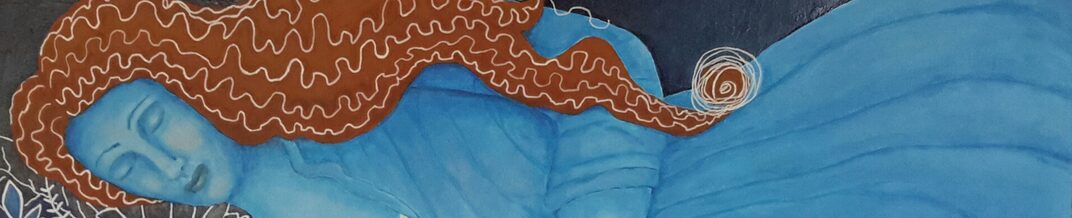

Bolton's paintings take us into a peaceable kingdom of dreams, reveries and earth -motherly potential. Her women are goddesses by any definition. They manifest divine strength and power as well as fertility, love and devotion. They are gentle and nurturing.

Yet despite their sanctity they retain an earthy wittiness. This allows them to be approached (respectfully, of course) as dependable and sympathetic allies, giving these pictures a kind of votive authority.

Her dream paintings are glimpses into the world of her unconscious. See, for example, "Dreaming of My Garden," "Dreaming in Blue," and the remarkable "My Dreams Make No Apologies," a title Paul Gauguin would have loved. She says:

"My dreams and my creativity are powerful forces in my life. During the creative process I often feel a sense of prayer, a sense of something beyond myself.

As far as my dreams are concerned, they are often filled with vivid colors and a feeling of pure joy and playfulness. I think this is reflected in the paintings in the choice of colors, choice of subject and my belief in the importance of setting aside the serious adult demeanor for a bit."

Commentary by Warren Obluck